Interview with Anna Dumitriu on Bio-Art and Science Collaboration

16th September 2025

Anna Dumitriu discusses her current exhibition in India, her bio-art practice working with epigenetics and infection prevention, and her ongoing collaborations with scientific institutions.

The interview was conducted by Geoff Davis on September 16, 2025.

Part I: Current Exhibitions and Projects

Anna, you've got a current exhibition in India, is that right?

Yes. It's at the Science Gallery in Bengaluru, India. It's part of an exhibition called CALORIE exploring our complex relationships with food. The show is on now and will continue for around 1 year.

https://calorie.scigalleryblr.org/plan-your-visit

https://calorie.scigalleryblr.org/exhibition?e=manna

My work in the show is called Manna: Epigenetics, Conflict and Intergenerational Trauma. It's rooted in research into epigenetics - the study of how our behaviours and environment can cause changes that affect the way genes work without altering the actual DNA sequence.

Could you explain that a bit?

Sure. Every cell in the human body carries the same DNA, but the way those genes are transcribed differs. That's epigenetics - it's about how the DNA is wrapped up in the cell and its chromatin structure, specifically how environmental factors affect which genes are expressed.

There is a significant historical case study linked to epigenetics which looked at the Dutch Hunger Winter cohort of 1944–45 (Dutch Hongerwinter). During the Second World War, the Nazis punished the Dutch by blockading food after a railway strike in support of the Allies. At least 19,000 people died of starvation. People ate tulip bulbs, chicory root, sugar beet—anything they could find. Children were sent out with spoons, hoping for a bit of bean stew. Films of that time are very tragic and moving. https://youtu.be/8rTom2mxLJI?si=3-ZVmDRq2O2zrkpN

Eventually, the famine was broken by Operation Manna - Lancaster bombers from the UK dropped food parcels, and ships from Sweden brought flour. Manna famously means 'food of the gods' but the title of this work references the military operation too.

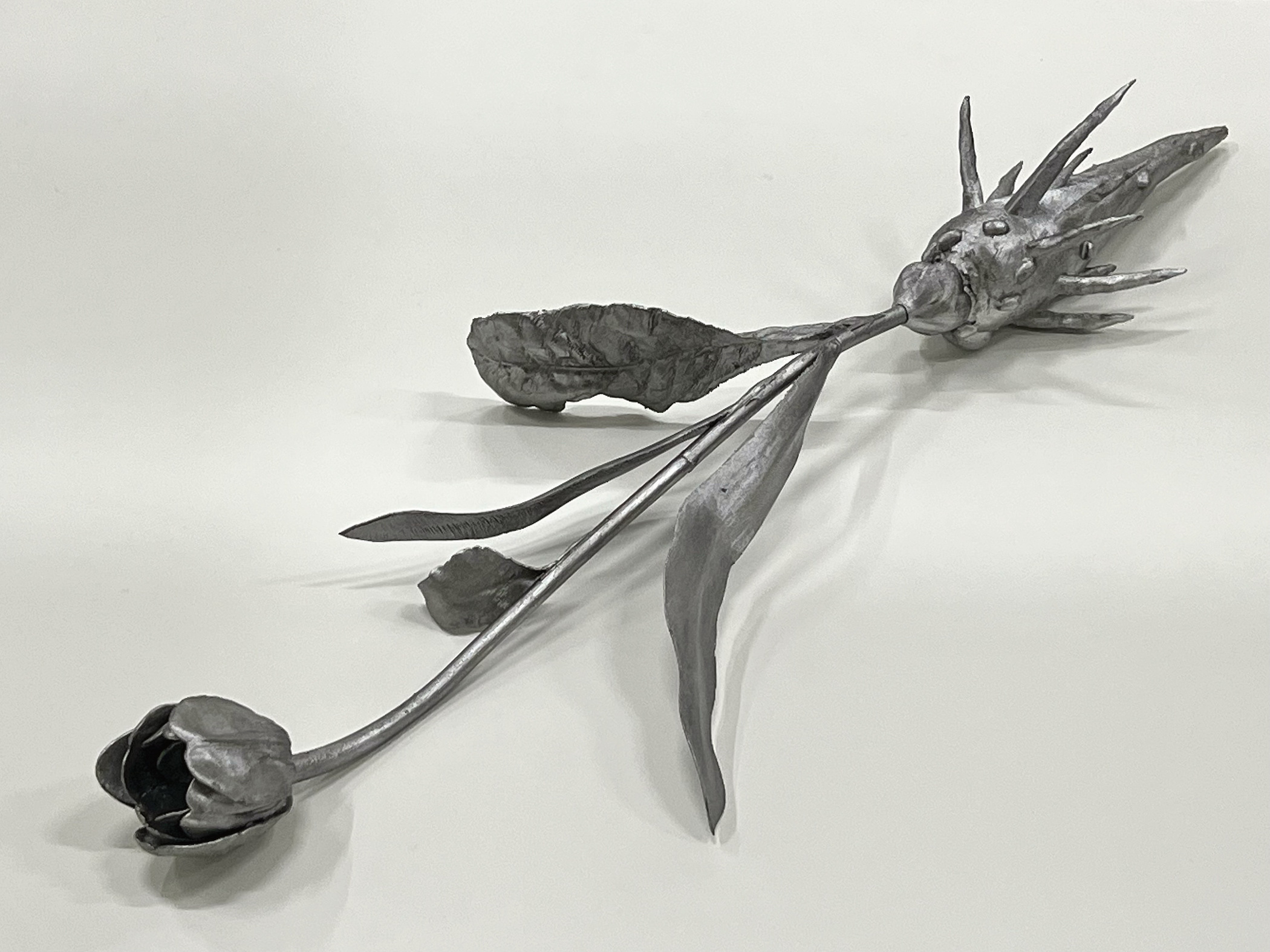

Manna: Epigenetics, Conflict and Intergenerational Trauma, Bengaluru India 2025

And there was also a scientific study of that famine?

Exactly. Because the famine lasted only a few months, it gave scientists a clear cohort to study. Babies who were in first trimester the womb during the Hunger Winter seemed healthy at birth and were born at normal weights, but as adults they were found to have epigenetic changes. In particular, modifications to the PIM3 gene, which affects metabolism. This meant they had slower metabolisms, gained weight more easily, and had higher rates of type 2 diabetes.

So, your artwork connects to this history?

Yes. The sculpture Manna: Epigenetics, Conflict and Intergenerational Trauma https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/manna-epigenetics-conflict-and-intergenerational-trauma/ is a kind of monstrous tulip: part tulip bulb, chicory root, field beans, potatoes, and their leaves—all photogrammetry scanned, and 3D printed (with help from creative technologist Alex May). Inside the tulip flower there's a 3D printed model first-trimester foetus actual size. I worked with the Institute of Epigenetics and Stem Cells (IES) at the Helmholtz Zentrum to incorporate the DNA of the PIM3 gene, which is painted on (invisibly) to the model of the foetus – to represent how these lives were invisibly marked by the impact of war and famine. I previously undertook at 4-year residency with the IES and produced my series The Mutability of Memories and Fates. https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/the-mutability-of-memories-and-fates/

The piece also engages with ideas of Postmemory - a concept from Holocaust studies that describes how trauma passes through generations, culturally, as well as biologically through epigenetics.

That's powerful. How big is the sculpture?

The sculpture Manna: Epigenetics, Conflict and Intergenerational Trauma

About 65 centimetres long. It was premiered in India, but there are now two versions. We're planning to show one at King's College London with my project collaborators there soon. I worked on the project with Professor of War and Society, Rachel Kerr, and curator Cécile Bourne-Farrell from the Department of War Studies at Kings College London to develop these ideas, and Professor Maria-Elena Torres-Padilla from the Institute of Epigenetics and Stem Cells was the project's scientific advisor. I worked with Jose Bautista to produce the DNA of the PIM3 gene.

PIM3 gene

You also ran workshops alongside the show?

Yes. In the Netherlands I ran workshops where participants made moulds from 3D printed first trimester foetus models and then made casts using biomaterials, specifically a kind of salt dough from Swedish wheat flour which was mixed with famine foods like tulip bulbs and chicory. In Bengaluru, we adapted the workshop to explore foods consumed in India in times of famine: banana stems, millet, things eaten during famine. It opened up conversations about famine, type 2 diabetes, and epigenetics in different cultural contexts. We also discussed notions of Postmemory in relation to the Partition and the Bengal Famine and the use of famine as a tool in conflicts. It's something that we can also see happening in the world today.

And what was the response in India?

Very positive. The Science Gallery is huge – probably bigger than the Hayward in London—and they get around 100,000 visitors per show or more. People loved the workshops and the talks, the audience was very engaged.

Part II: Future Projects and Scientific Collaborations

Looking ahead, you've mentioned King's College London. Are there other projects in the pipeline?

Yes. I'm working with Dr James Price at Brighton & Sussex Medical School on their research into creating an AI system for infection prevention where AI predicts who might develop an infection such as MRSA and suggests preventive actions in advance of the patient actually catching the disease. The artistic project (which is a collaboration with Alex May) responds to this work and explores novel new research which offers to improve infection prevention and control (IPC) in hospital settings using artificial intelligence. We are exploring how the NEX AI infection prevention system works by applying it to an AI expanded historic data set based on John Snow's research on the 1854 Cholera outbreak in Broad Street, London, considered to be the first epidemiological study ever conducted.

Alex and I are making a body of artworks in response to this using all available AI tools to visualise and expand datasets for this. https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/ai-and-infection-prevention The initial work from this was just show in the 16th Triennale Kleinplastik in Fellbach in Germany. https://artfacts.net/exhibition/16-triennale-kleinplastik-habitate-ueber-lebensraeume-stadt-fellbach-kulturamt-fellbach-2025

I also recently did a residency at VIB-KU Leuven's Centre for Brain Disease and Research, developing projects around brain disorders. https://cbd.sites.vib.be/en#/

Have you always worked in bioscience contexts?

I was trained in fine painting, but since the early 2000s I've been working hands on in the lab with microbiologists, synthetic biologists and medics. I was artist-in-residence at the Centre for Computational Neuroscience and Robotics at Sussex (CCNR) from 2004-10, and from 2010 at Modernising Medical Microbiology at the University of Oxford, which continues to this day, I am also currently artist in residence at Leeds Biomedical Research Centre and with the Wellcome Sanger Institute https://annadumitriu.co.uk/biography/

You've also got pieces in the Drivers exhibition?

Yes. One is Susceptible, https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/susceptible/ an interactive installation about antibiotics and tuberculosis, made with Oxford University's CRyPTIC project. For the exhibition, I produced a 2D satin print of a still from the installation, with hand-beaded details.

The other is Precious Cells, https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/precious-cells a still from an interactive browser-based artwork which was a collaboration with the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge, pioneers of IVF. It's about embryos donated to research which are in short supply, and considered very precious. I created golden 3D models of early-stage embryos, floating in a watery installation environment. It's about how both the science and patient communities see these cells as deeply valuable.

Part III: Working with the Computer Arts Society

How is it working/collaborating with the Computer Arts Society (CAS)?

I was introduced to the history of Computer Art through Professor Paul Brown back when I was artist in residence at the CCNR and following in his footsteps and was instantly fascinated. You can see that my work is constantly making threads between history and the future, culture and science – so it really fitted with my interests. Before becoming a committee member, I co-curated two exhibitions in collaboration with CAS: Intuition and Ingenuity https://turingcentenaryarts.tumblr.com/exhibition https://www.bcs.org/articles-opinion-and-research/an-artistic-turing-test which included artists who were inspired by the work of mathematician Alan Turing (for the 2012 Turing Centenary for which I was co-chair of the Arts and Culture Committee), and Technology is Not Neutral https://technologyisnotneutral.com which featured women (across generations) working with digital arts. Now I work with CAS to raise awareness of the fascinating history of Computer Art, and in particular older artists whose pioneering work is under-recognised, and also to ensure CAS is reaching out to more diverse audiences of all ages and backgrounds.

Thank you, Anna.

Thank you, Geoff.