Interview with Catherine Mason on Creative Simulations

28th July 2025

Catherine Mason talks about her new book about George Mallen and the Computer Arts Society, and ECOGAME.

The publisher Springer currently has 20% off using code SPRAUT - https://bit.ly/3xdOE58

The interview was conducted by Geoff Davis on July 28, 2025.

Part I: The New Book

What inspired you to focus this new book specifically on George Mallen and his role in the Computer Arts Society? Was there something about his work that felt especially urgent or overlooked in the broader history of digital art?

This is an exciting time as the canon of art history is starting to broaden to include the history of computer arts and the relationship of art and technology in the 20th-century in general. Of course this means some practitioners risk being overlooked. Canons by their nature are about inclusion and exclusion. I really believed that George Mallen's contribution as a great innovator in the field of creative computing since 1964, ought to be better known. Mallen is a self-effacing person who quietly got on with things throughout his long career, without loudly blowing his own trumpet. It was nice to kind of subvert that cliché (unfortunately often true) about those who shout loudest getting the most attention.

Ecogame at Computer 70, London, also Davos, 1970 - see below

How would you describe the ethos of the Computer Arts Society (CAS) in the late 1960s—and how does it differ from today's digital art scene?

Well, in those days, pre-Internet of course, it was a much smaller world. CAS was formed by three like-minded people from diverse backgrounds (Alan Sutcliffe was a programmer, George Mallen a physicist and behavioural scientist, and R John Lansdown an architect) who saw that digital technology was probably becoming the most outstanding thing to happen to humanity. With a very open mind-set, they wanted to explore the impact it might have on the arts – from visual, through sound, poetry and text, to performance. One of their initially stated aims, that I especially like, appears in the CAS booklet of 1969: "To foster methods and systems that suit people and to resist the tendency to make people fit systems". Although there were other groups like E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) in New York and GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel) in Paris, to name two, CAS was the first practitioner-led group to focus specifically on creative computing. Fairly quickly there were 1000s of members with a regular publication – PAGE, discussing the main issues and featuring the work of members. It had an international reach with members based in North and South America, Europe, Japan and Australia. For a short while in the 1970s, there were branches in Holland and the USA.

Obviously, the digital art world has now expanded massively and is more widely distributed globally. The tech has become more powerful and cheaper; it's also more accessible and inclusive, anyone with an Internet connection can participate. NFTs and social media have also made a huge difference, meaning that artists can now reach collectors directly and bypass the traditional realm of dealers and galleries. Computer artists of the 1960s to 80s found it very difficult to get accepted by the artworld networks of dealers, museums and auction houses. Today these things matter a little less (although I'm sure they are pretty nice to have!). Unlike the early days of CAS when it was possible to know almost everyone in the field, today there is such a huge proliferation of practitioners, artworks, exhibitions, books, podcasts, posts, and so on that I find it impossible to keep up!

Did CAS see technology more as a tool, a collaborator, or something else entirely?

The amazing, and unique, thing about CAS throughout its history is that it always encompassed a wide range of approaches to technology. The founders (Sutcliffe, Mallen & Lansdown) deliberately used 'Arts' in the plural to include all aspects of human creatively that could be impacted by computing. Many of the early members were interested in algorithmic coding and a systems approach within a tradition of Constructivism. However, there was a variety of opinions and techniques, at least within the limited power that computing held at the time. (Some artists did give up making art with computers because the technology wasn't powerful enough for what they wanted to do). Initially, you did have to learn to write your own code and construct or adapt your own equipment, especially output devices like plotters, so people did tend to have these interests in common.

In the late 1960s artworld there was, still, demarcations between disciplines, and a hierarchy – a snobbishness really, for certain kinds of practice or certain types of practitioners. For example, there were, in many people's minds, strict distinctions between fine art and craft. There were also established conventions defining who or what an 'artist' was: art-school trained and a lone genius probably working with paint and probably male (although women did make computer art, society was more patriarchal then). Computer art, being interdisciplinary and involving as it did people from science, mathematical or technical backgrounds, subverted these norms about who was 'allowed' to make art. (Jasia Reichardt made this plain in her ground-breaking show Cybernetic Serendipity of 1968). These are some of the reasons that made it problematic for art history.

Could you walk us through Ecogame—what made it so innovative at the time, and what might we learn from it today in terms of interactive systems or ecological thinking?

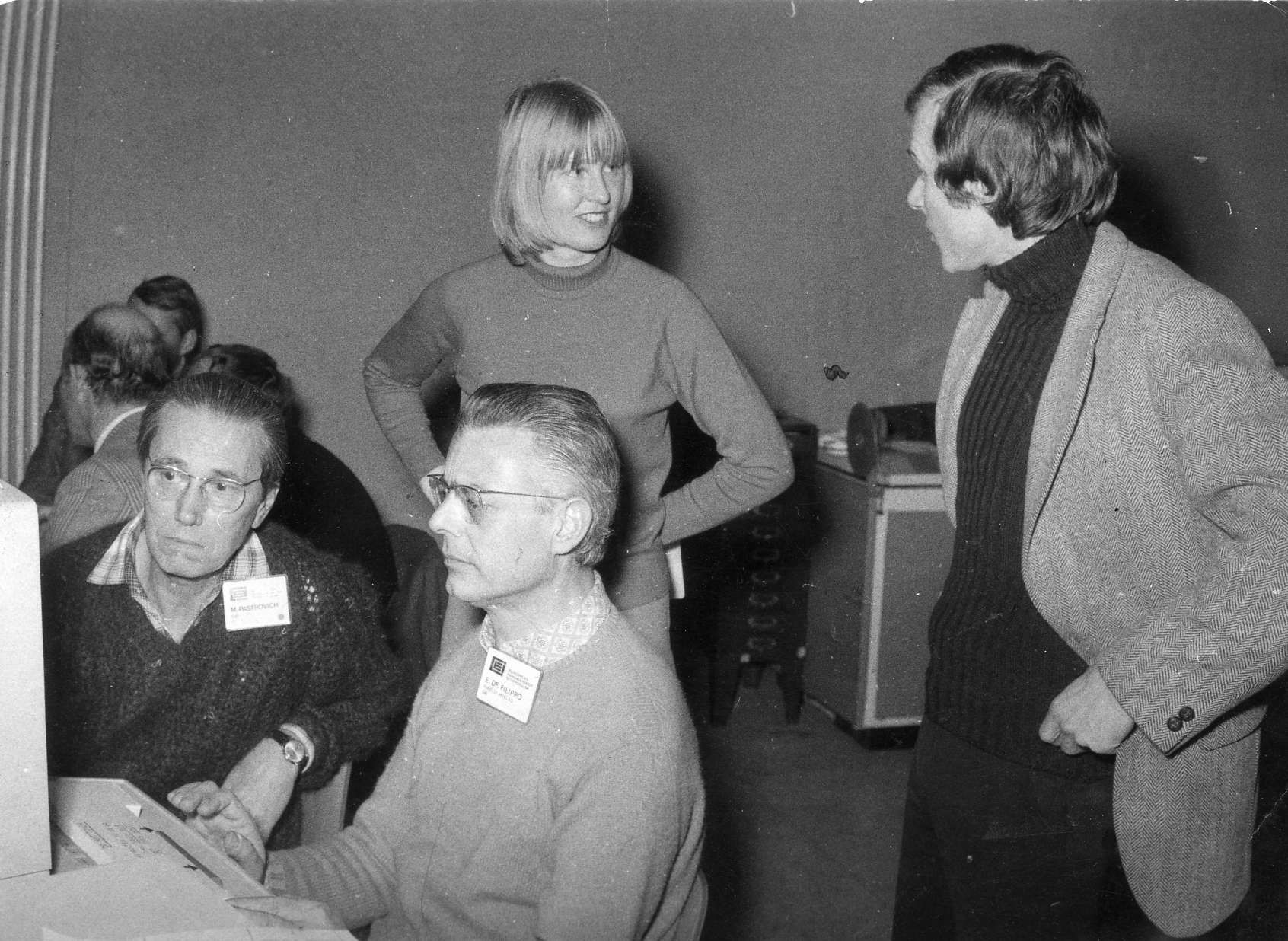

Sarah Mallen (standing, centre) with Ecogame participants at Davos 1971

Ecogame was an ambitious, cooperative project involving around 25 CAS members, led by Mallen. It was a simulation model of an economic system, with the theme of competition and cooperation. It dealt with opportune issues of ecology and environment (the Eco of its name) and how both could impact human decision-making. It became the first multiplayer, digitally driven, interactive gaming system in the UK. It exemplified the CAS belief in a positive 'human machine interrelationship' made visible through art. It was several things at once: a work of procedural art, a theatrical performance and a piece of conceptual art where the notion of an active audience becomes an integral part of the creation. It was seen and played by 5,000 people, exhibited in London in 1970, then at the first iteration of the World Economic Forum in Davos in 1971.

Players made choices in answers to questions and the effects of these decisions was shown pictorially on screens displayed overhead, from a bank of 720 35mm slides. These images varied depending on the general level of affluence in the economic model under the control of the players and the relevant prosperity or effectiveness of the individual players. The player/participants became aware of the impact of personal motivation versus commonwealth, differential distribution of income, and personal sense of agency within the overall system. Many of the questions related to the oil industry – something that was very much in the news then and still is now.

Delivered over a live network (connected to a remote time-sharing computer via telephone lines), Ecogame's hardware consisted of nine Tektronix graphics terminals - the first such terminals in Europe with tracker ball interaction, using recently invented acoustic couplers. Additionally, an Idiom minicomputer-driven interactive graphics system with large screen and light pen interaction, was also linked to the remote computer using an acoustic coupler. This was the first time such tech had been put together in this way - a very impressive feat for 1970!

Some aspects of Ecogame can be seen in today's artistic use of virtual reality, augmented reality, serious games, immersive environments, and so on, but really it was of its time and as such its own unique thing. This is not to say that those conceiving it and working on it were not incredibly innovative in their thinking and implementation, but they exploited the tech available to them to address issues of the day they were concerned about. Mallen did say that the system could be adapted to the concerns or desires of anyone. This is one of the great things about adopting a cybernetic approach from start.

See "George Mallen and the Ecogame" in-depth article (July 2024).